Watching scattering snowflakes from the passenger window, they swirled and looped, taking their own time to land. The dance they performed was a gleeful dance of teasing the brown dried husks of corn, bending down to touch them, then letting the wind carry them back up and around, a bait and switch that nature plays with itself. When they landed, we are already further down the state route, onto the next corn field, the next barn emblazoned with fading Mail Pouch Tobacco signs, another trailer park on the road from the parsonage I lived in, mostly by myself that final school year of 1985-86 to my mother’s new house with her boyfriend in Galion, Ohio.

I was in that difficult space between childhood and manhood, where I was not quite ready to be on my own but so close I could taste the freedom that eighteen brings but still dependent on people I was still angry with. This predicament made me angrier, more resentful as I most did whatever I wanted to do but when there were times I couldn’t, when my mother would wave her wand of matronly responsibility, I would seethe inside. A blend of anger mixed with a yet-unknown silent hurt of her abandoning me once more. She had picked me up in Catawba, my stepfather back in the psychiatric hospital 50 miles away from home, she wanted me to see her new house. A condo she was renting with Steve whom she had met at Maryhaven a rehab center in Columbus. She an administrator and he an alcoholic/drug user who was trying for what felt like the hundredth time to quit. I had never met him and was none too pleased to be meeting him this weekend.

She talked to me from her side of the car while I stared outside the window at all the things that make an Ohio winter something that is as desolate and terrifying as the dead-end future can be for kid that only wanted out of everything that small town Ohio could offer. All of which was basically fuel to want something different. My eyes burned, there wasn’t a catch in my throat but more of a fireball that I kept inside lest it erupt into the front seat of that blue Chevy Cavalier and turn my mother into a stammering, crying puddle. I knew her limits. I just listened and looked. We arrived in the small town of Galion, in the center a small courthouse, gas stations, hardware store, a feed store at the edge of town my thoughts drifted to my girlfriend who I would have to wait to see in a few days. I pined for her. My mother brought up me moving up for the rest of the school year, “no way,” I replied, “I’m not living in this shithole of a town. I’m almost done with school, so I’ll just finish it out.” Sighing in a way that she perfected, she put her hand on the back of my left hand. I flinched, taking her hand away she softly asked me “think about it. I think you will like Steve.” I rested my head against the window, feeling the cold glass against my forehead, “Jesus Christ mom, you are still fucking married” in a whisper she would be able to hear. We drove the final few minutes in silence.

Steve opened the door to their new condo, it had new furniture and Native-American art on the walls, and Steve had a small stereo in the corner next to it was a large wooden cassette holder and a stack of worn LP’s underneath it. This caught my attention and Steve came out of the kitchen and shook my hand, “I’ve heard a lot about you, your mom says you are pretty funny and like music.” “Sure” I headed towards the bathroom with my lungs in my throat and heat rising in my cheeks. The bathroom was decorated with a candle, sea shell molded soap and new hand towels. This was nothing I had ever grown up with. It smelled like cherry blossoms. As I splashed water on my face, I noticed my hands were shaking, I wanted a beer but they wouldn’t have any. Steve was sober.

That night we went out to eat in nearby Mansfield, to a chain casual dining place—maybe it was Applebee’s, TGIF or something like that, it was the sort of place I had never really ate at as we were poor, going out to eat was only done if we drove to Columbus to see my grandparents and uncles. It was small talk, Steve mostly remaining quiet while my mother asked me about school, my girlfriend and filling out college applications. “I dunno mom, maybe I’ll go to someplace near Columbus.” “I thought you were going to go to OU, that is what you have always said, to go home to Athens. You could live with the Zudak’s” The Zudak’s were my middle school best friend, Eric, his older brother and sisters and his mother. Eric’s father had moved out of the house a few years before and I would go down to Athens on most of my spring breaks throughout high school, wander around town, hitting the bars and drinking in shitty cars. “I’m not sure”, I wanted to near Jennifer who was going to Ohio State. “You could move up here with me and Steve and go to a community college?” “Mom, stop I’m not going to live with you.” The rest of the dinner was quiet and when we got home, I went to bed. Over pancakes as we went out to eat (again!), Steve talked about music not really asking me what I liked but sharing how much music meant to him. “When I moved to Columbus, I probably spent more time going to concerts than I did in class.” “Oh, who did you see?” This was a test, in retrospect it was really a test by Steve to try to understand me, not win me over—he never tried to do that. His goal was to identify with me, he understood I was deeply wounded in my childhood, much of it by my mother even though I had very little insight into this hurt which at this time in my life mostly manifested itself as anger, frustration, and quiet rage. “I saw Lou Reed at the Agora, he had bleached hair and wrapped the microphone cord around his wrist like he was going to shoot up some dope. I thought that was the craziest thing I had ever seen.” “Steve, he doesn’t need to hear that” my mother piped in. Rolling my eyes, “mom I know what dope is, and Lou Reed is one of my favorites. Who else did you see?” I was impressed. “I saw the Rolling Stones in Cleveland on Mick Jagger’s birthday and they played so long they cut the power on them, I thought there would be a riot. There was a giant inflatable penis that went over the crowd.” Many years later he told me he was on acid at that Stones concert. We talked a little bit more, he had seen The New York Dolls, the Velvet Underground, Kiss opening for the New York Dolls, Neil Young, Dylan; so many artists that I had discovered during high school. That day we went for a small walk around the town, I begrudgingly realized I liked my mom’s new boyfriend.

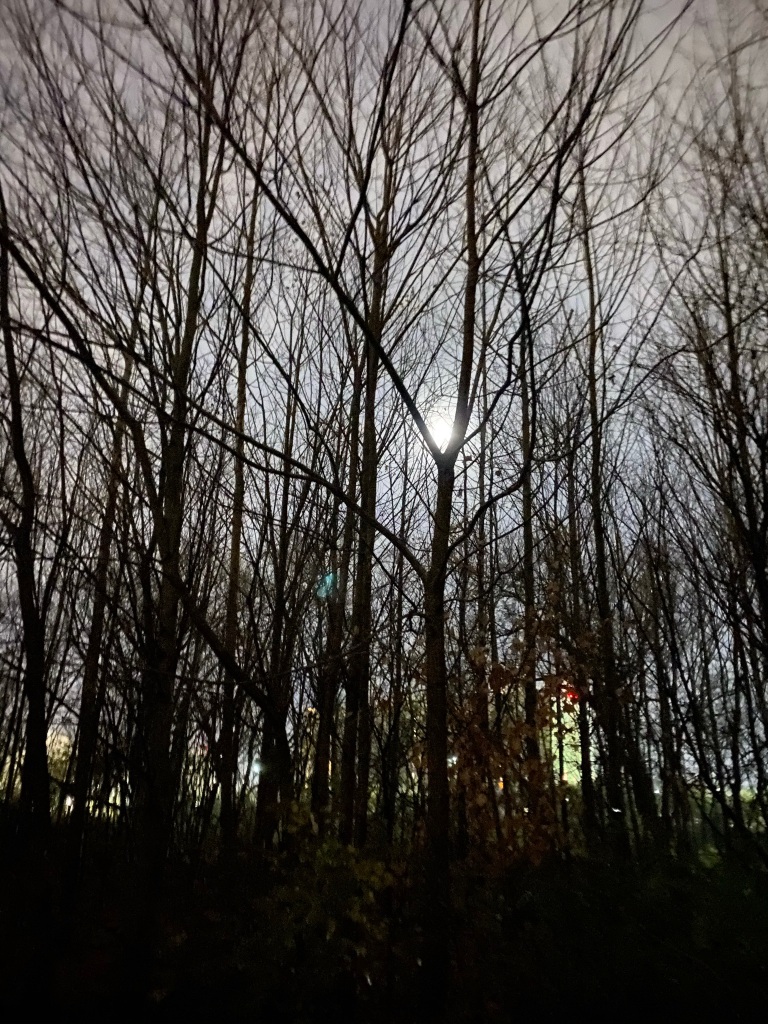

On the way back from walking my mother and I argued, “just take me home.” Feeling like a dog in a cage, trapped and annoyed that I was helpless and at her mercy. “I don’t want to be here no matter how much you think I will like your new life, I don’t give a shit. Take me back.” In her bedroom I heard my mother cry, mournful wails and I felt no pity for her, no remorse. Eventually she came out of her room, face flushed, eyes reddened from crying. “Steve is going to drive you back, I don’t feel well enough to make the drive.” A part of me felt a tinge of being abandoned yet again, “Ok.” But what I was thinking was, “fuck, you are going to have your boyfriend drive me back to the empty house I share with YOUR husband? You are kidding me?” I swallowed that thought and fetched my clothes from the spare bedroom. Steve had a small pick-up truck, we rode in silence except for the tapes he let me feed into the dashboard, John Prine’s first record, David Allen Coe’s greatest hits, Dire Straits, and Lou Reed. He dropped me off in the alley next to the parsonage, snow gentling falling around me as I got out of the truck. Steve leaned over, “Nice to meet you Bela, your mom really loves you.” He drove off as I turned towards the house, darkened and empty, a place that was home but never really felt like it.

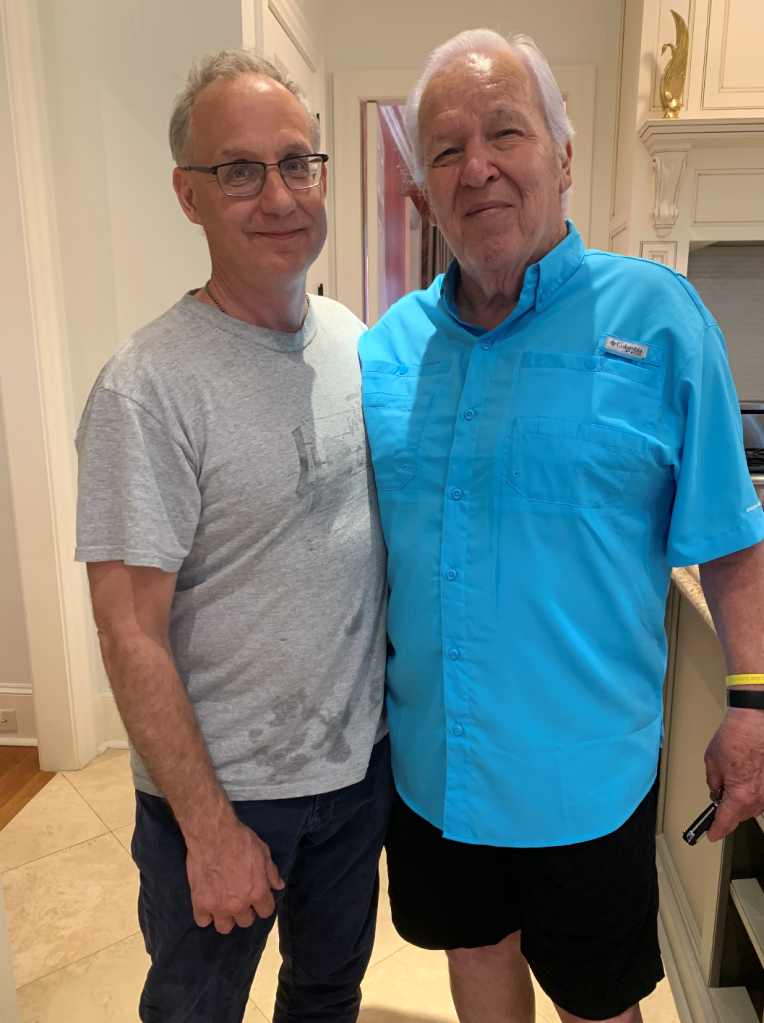

Over the years as we all worked our way into time as if it were a field of sawgrass, cutting our ankles, a slog into middle age for me and a slow sunken decline towards death for the generation before me and my siblings. There were break-ups, fuck-ups, children and my own struggles with misty sorrow that has seemed to follow me like a sick-feral cat. A walking disappointment was what I felt like much of the time, even though I had enough confidence in myself to live the kind of life I desired (mostly consisting of music, drinking and laughter). But when it came to my family, I would have sooner not have to let them into my world. The fact that I didn’t really attend college but opted to work in a record store, which didn’t seem like work at all—either to myself or to my family. My mother, father and my brother would pine for me to try college again, Steve never did, just encouraged me to do what I liked to do, “Susan, he will figure it out for himself and if he needs you, he will ask you.” This was as true a statement as has ever been said about me, Steve was the wisdom of our family. A solid towering tree that stood tall in the middle of our brushfires, he felt the wind at the top of his branches and the cold of the winter in our lives, I was gifted to come and sit among the wooden limbs without ever feeling judged. I never heard him raise his voice and living with my mother was a way to practice dealing with frustration on a daily basis.

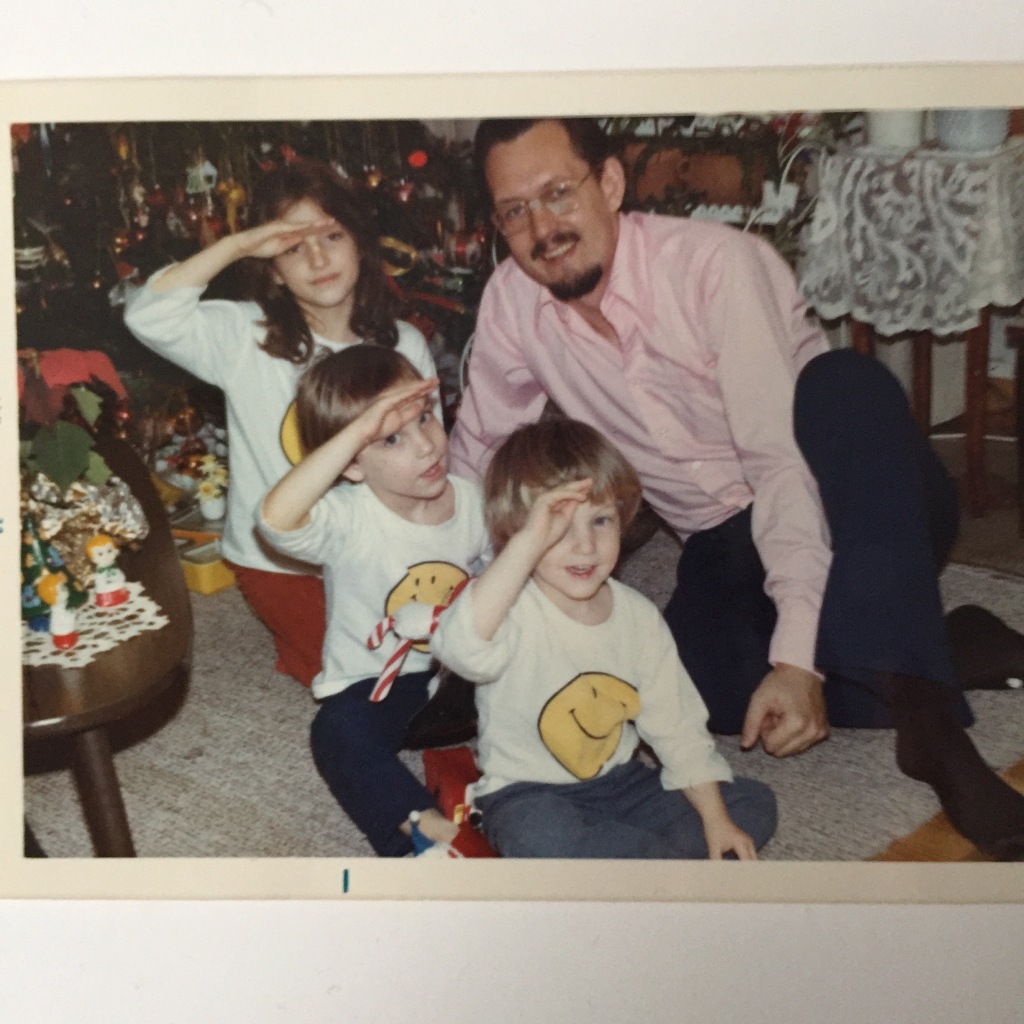

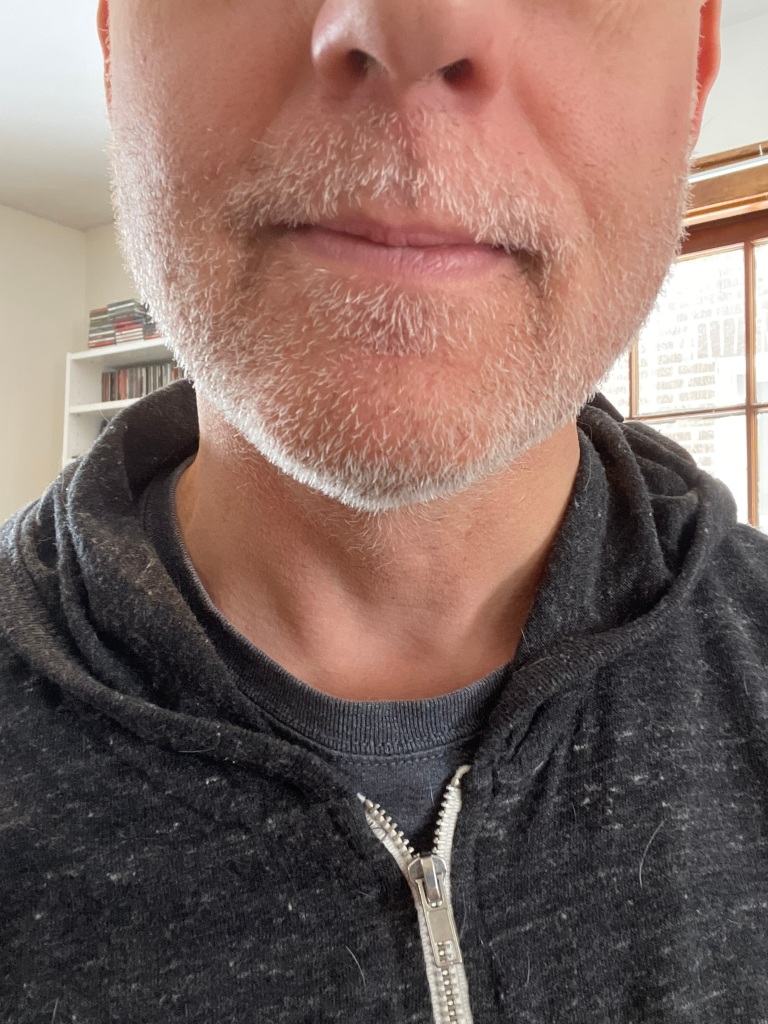

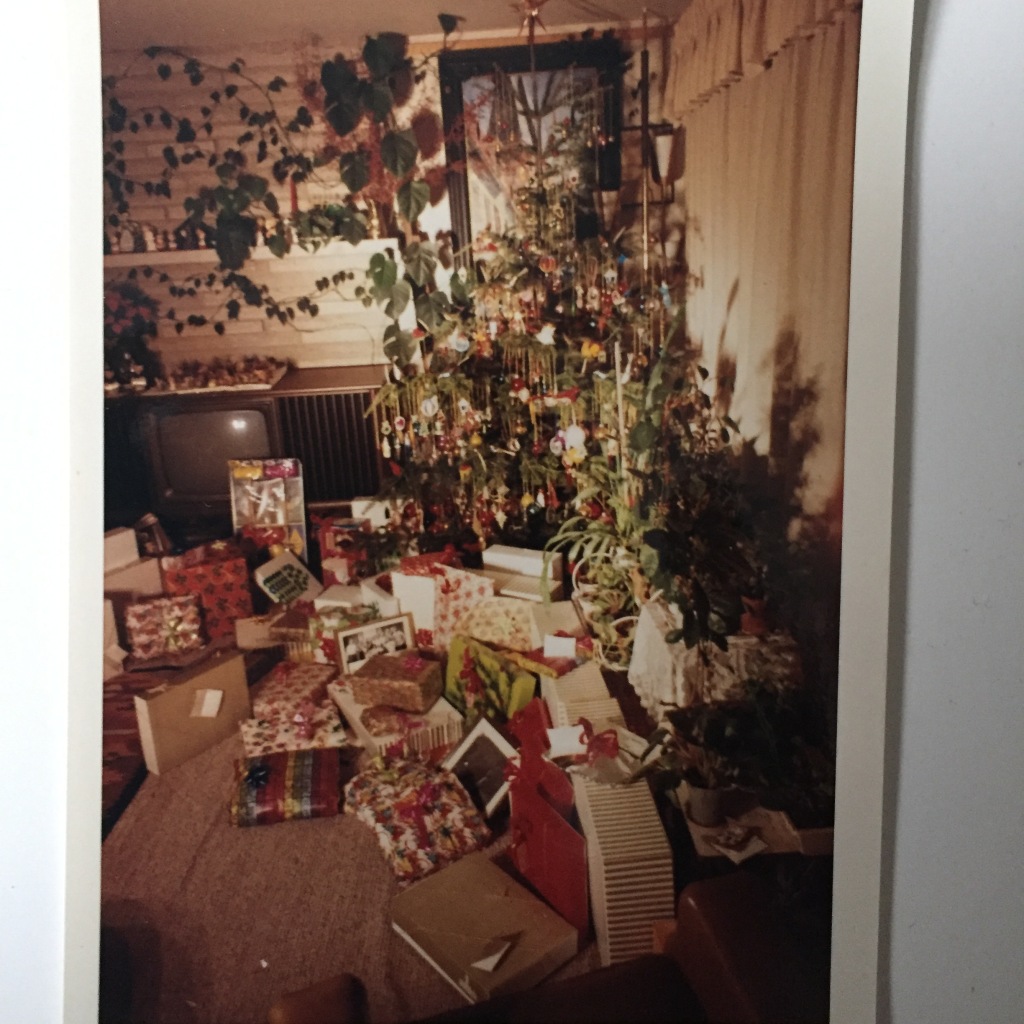

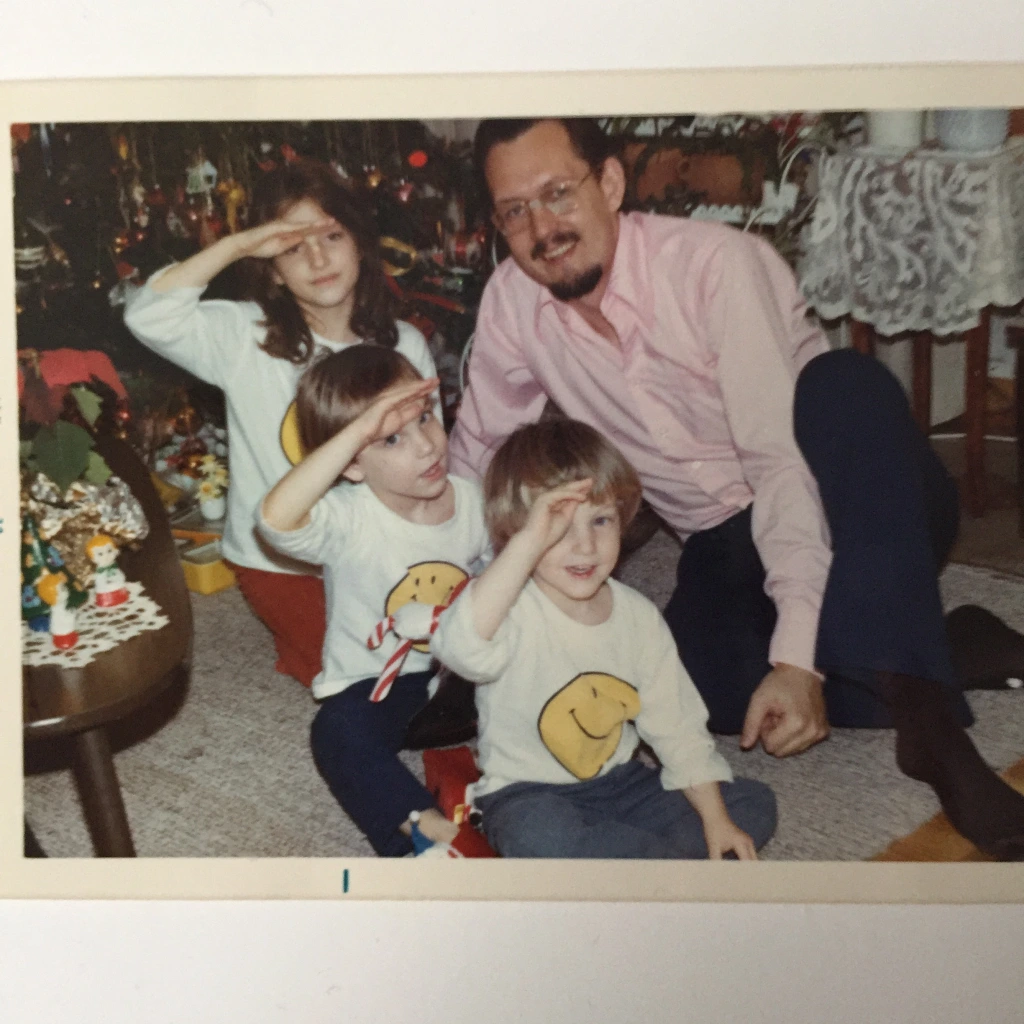

Time is tracked in various ways, tracking the stars in the universe their flickering light coming from billions of miles and billions of years from the past and as their lights land upon the eyes of stargazers many will have ceased being billions of years ago. Their sparkles a sort of gravestone etched in the sky for us to gaze up. We mark time through the books we read, a collective history made from the drawing in caves, on stone walls, through the ancient Egyptians utilizing papyrus over 5000 years ago, to the development of papermaking by the Chinese to the present where digital pixels contain the entirety of humankind at the touch of fingertips. I tracked the age of my children by pencil, every six months they would stand still against their bedroom wall or against the door in my bedroom apartment while I drew a straight line at the top of their head. These inch increments showed them how age can be measured, they quit doing it a few years ago and my son, aged 15 is now taller than me—it is as if the tracking is no longer needed; he has won the contest. Boxes of photographs fill my basement and in corners of my house, shoeboxes, wooden boxes and cardboard boxes carry the information of my past, the past of my ancestors stacked upon one another as if they were ping-pong balls in a lottery machine. Black and white, Polaroid and faded colored photos from the early 1970’s that have grown their own age spots, blotted with fuzzy white and yellow globs that may overtake my siblings, myself and Santa. My whiskers are mostly white now, if I don’t shave then I will look my age so I run the razor over my skin, the skin that is not as tight as it once was and with that razor I make myself younger, anyway this is what I believe. So many ways of tracking time although in my mind I see the universe swirling like a giant whirlpool swallowing up everything all at once, and in this grand whirlpool people are smaller than a droplet of water rushing over Niagara Falls and then become mist. And when I die, my memories die with me and perhaps for one or two generations I will be remembered for a few things in my life but not for the mundane or what my daily interactions were like, not the cuddling of my dog nor the pride in my children or the laughter I was a part of, so much laughter that it caused people’s head’s to turn. I track the days of Steve’s death by my memories of him, there are moments when I breath in and at the bottom of my breath in the tiny flicker where it stops before turning inside on my out breath, it is in that speck of time where I feel a panic and I yearn for him, for my mother the most.

I have a dream, a recurring one that sometimes comes in different scenarios, always weird because dreams are strange, baffling, and weird, it is the very nature of dreams. As if reality is witnessed through a cracked kaleidoscope. In the dream I am leaping into the ocean, sometimes I’m wading in with the sun hot on my face, other times I am heaving myself into the water from a dock or a boat both and sometimes it is from a cliff like the Mexican divers who hurtle themselves over the rocks below to split the waves in half. The split is spitting into death’s face, “take that mother fucker.” I leap into the water and break the waves and then the waves break me, so they think but I’m already broken. Not whole. Not half, but a million shards of me, each one reflecting something else and in the ocean, they look like diamonds scattering in every direction, carried away.

Steve lives through my body, my thoughts, this is what I like to believe and when I play the music, he so cherished I feel him in the notes, the yelps of the singers and the bubbles of sound that carry me to a place where I usually feel safe. I know he listened for the same reasons I did, for comfort, for connection. Nobody dies instantly, we all die and live by degrees. Some are just closer than others, some can taste the bitter richness of whatever that unknown darkness carries. I miss you Steve, perhaps more than ever.