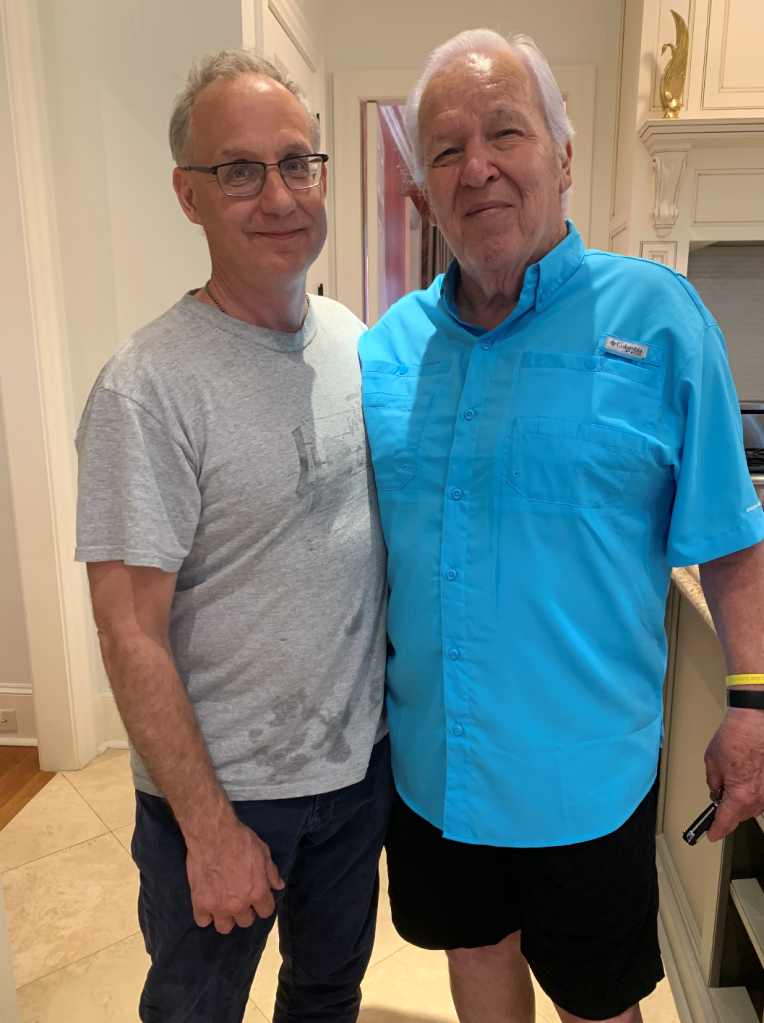

March 8 2002-March 8-2022.

When the sunshine brings itself into the house, dust floats both up and down, circling the room as if air were water and each particle was a miniature fish swimming through the living room, the dining room and everywhere—it is teeming with dust. There is little anything to do about it, the old apartment had a furnace at least forty years old, parts of it incased in asbestos and one reason the rent is so cheap is because of the effort it would take replace it. We all die every moment, some die just faster than others. Have at it asbestos spewing machine. The flowers add color to the shelves and stacks of books, the walnut furniture and, of course, the giant wall of records and compact discs that line the walls of the dining room. They demand attention, and why not-they most likely have saved my life on many occasions. Lifting my mood or matching it, tiny grooves brought to life by a needle and electricity. I have heard that the majority of dust is human skin, my house would seem to have the skin of every inhabitant that has ever walked the scuffed wooden floors the past hundred years, long after people die parts of then literally continue to swim around us.

There are days that tug at me from the inside, pulling around the ankles of whatever it is that rests and propels me forward. A soul? A conscious? A sub-conscious? A river of tiny electrical outlets connected by cells and nerves inside my body? A tug this severe can be an ache, and over the years, it started around the age of nineteen, hit several peaks when I was twenty-one, thirty-three and fifty—these peaks towered above me, but they were the edge of annihilation, like wind slicing through the branches—the ache can be violent or soft, almost undetectable except for the small wisps of the leaves. It is those moments I crave, when it is silent, more of a whisper than an insurrection in my mind—repeating itself like a 100-person choir coming to the chorus now. I have resisted joining the choir for most of my life, and at other periods the metaphorical church doors were closed and my hope was that it was demolished, wiping out the sounds. The Depression (it deserves a capital D) was planted in me before I was born, like cicadas already burrowed deep in the ground before my parents even met, it has existed in our family genes much longer than I can even guess—and for some in our family it has sprouted inside of us as if it were a doomsday vine, roots growing inside, and as we have aged so has the vine, its arms reaching deep into our psyche and some of our experiences sprout new buds. At various times in my life, I have been able to prune it, through love, through mediation, music, writing, running and through the past two years walking several miles every day. But the roots are there, entangled at my core, one person I know compared it to a giant pool of black water that feels I am drowning in.

The asphalt basketball court at East Elementary was baking from the spring time heat, balls were bouncing in an out of the baskets, in the far corner of the court, a small courtyard held a particularly vicious game of dodge-ball, the thick plastic red ball with its red bumpy exterior, zinging unlucky victims—red welts a testament to their lack of mobility, being slow on an elementary school playground can be a deadly trait. The hill at the other end of the court dipped down into the swings, the monkey bars and a giant half buried tractor-trailer tire that smelled of urine and the fidgety moments of first kisses traded after lunch. I had been a quiet child, moving every year had taught me to be silent, wary of friendships and I was always the smallest kid in my class—shy—I tended to stay to myself, keeping myself fortified with Marvel comic books and my early interest in the records I started collecting in third grade. The baseball field was dotted with fourth and fifth grade boys, swinging wooden bats—trying to impress girls and the other boys by knocking a leather ball out of the infield. I stayed back, if it were football season, I would have partaken in the boys’ games but, being small, uncoordinated with limited hand-eye coordination left me quite happily on the sidelines. There, on the side of the black sheet of play I found a voice that I would come to rely on for most days of my life. Several teachers, including Ms. Houska who would vacillate between calm and empathetic to being witchy and loud was there along with one of the student teachers, a blonde woman whose name is long gone and may well be a granny at this point, and of course, there were the other kids who didn’t play dodgeball, basketball, baseball or want to hang on monkey bars and had outgrown the metal swings the past few years. These were, for the most part- girls. In this moment, I developed an instant character, a sort of hippie who spoke in a high-pitched voice and while I didn’t really know what marijuana was, I pretended I was high-my voice a high-pitched sing-song voice—they all cackled. The student teacher doubled over in laughter, and as we sauntered back into class, I felt charged, a bit tired but excited. Several of the girls, one of whom I had a fourth-grade crush on remarked how funny I was, and I felt her eyes on me. From that day forward, I used humor to help placate the sense of isolation, an outsider in my own world that would later take the already seeds of depression into those blossoming vines that would later wrap and choke my life.

The clatter of the plates, knives, forks, a vase full of flowers surprised my first wife—“what the fuck is wrong with you?!” she screamed, our entire relationship was one long scream, her screaming, my screaming back at her, the broken bits of our house and squealing of tires. “You are fucking with me! Get off my fucking back!” I yelled back, shards of glass and ceramic on the floor— “Watch your step! You broke my plates! What the fuck?” tears streaming down her face, hands against the table-holding herself up. “Our plates, they are our plates!” I yelled back at her as I scrambled for keys and slammed the door shut. Soon, she would move out, the failed experiment of our short lived (more like deathbed) marriage abandoned in that small two-bedroom house on East Patterson Street. “You ruined my life” she said as her friends from work hauled out furniture, she got the keys to my small white Metro, and I was relieved that it was all I lost, the failure of the relationship sat on a throne in the back of my skull.

The months that followed were a period of shrill fear that I skidded through, nights at various bars, my bedroom floor littered with clothes and records, there were bottles of beer on every piece of furniture in my room, cigarette butts that had burned the corner of my dresser, the table next to my bed—somehow I was never alone—the feeling of being alone brought a desperation that motivated me out of my house. I was a wanderer in a five-block radius. I soon fell in love, and that relationship lasted over twenty years—with chaos, another dip into the deep black water that almost drank me up—a night in a motel contemplating the metal of a gun in my mouth that turned into sobriety that I still live today. There were trips all over country, to Europe which felt like a home I never really had, a house and of course, two children. That marriage ended in 2018, a period where the blackness came oozing to the top and although I was sober, I felt bereft of myself. At times, I would wake up in my bed, my small dog snuggled next to me turn my head and weep into my pillow—I forced myself to work, to exercise and to show up. She and I talk frequently, we have too—the children we created are the center of our lives, and when we part—sometimes we hug and the love the built the children is there, different of course-but there—and it stretches outward into the kids lives, dreams morph, like clouds and I am ok with this. When I see my children, I see all the love I ever feel walking, talking, making me laugh and of course, causing me worry.

Depression is something that is like a fog, but a fog filled with monsters, it pours outward like a gushing waterfall that heads for the ocean. At times it has felt like there is a snake trying to get out of my throat, but it slithers inside of me, choking me and it finally decides to stay, coiling inside of my guts waiting to spring out when the opportunity arises. Suicide is something that some people live with on an everyday basis, a taste that will not leave– like the bitterness of a lemon, but it never leaves. Add some sugar it makes it easier, but it only dilutes the acid. I get jealous of the branches on the trees that I stare outside my window, I imagine their bravery as the wind whips and rattles them year after year, and when the sun is out they drink it is as if they had never tasted shine before. Their roots hold them solidly, growing up into the sky and deep into the earth and then I walk in the woods and I notice the ones the collapsed under the weight of living too long, the wind catching it just right or a crack of lightening choosing to crawl up its spine and it lays on the soft floor of the forest, for the rest of the trees to see, it’s carcass now a home to insects, moss and critters. Of course they are just trees, with no mind to think of these thoughts that I transfer onto them. They have no eyes to see but they do feel in some ways, their roots communicating in what is called mycorrhizal networks, a language of survival they chatter to one another through fibers intertwining with one another, finding nutrients, water and the ability to let other roots where stones may be a barrier. The complexities of this provides hope, an opportunity to feel small for it is when I am small that I can experience the world, when feeling too full a person can’t learn any more. There is no room.

A friendly nod, followed by a cold bottle of beer being pushed my way, the cool condensation streaming down its sides was a comfort. An easy way to feel differently, to slip into something else from what I wanted, and predictable. For certain I knew what would happen when I tilted the bottle to my mouth, first the small smell of the alcohol seeping into my nose and quickly followed by the beer. I always took a long drink, letting the beer go directly to the back of my throat, my ability to drink almost half of the beer in one long drag off the bottle was a practice, my mouth craved the cold bath of five p.m. I learned without ever thinking of it. Most of my regular bartenders usually had another one set up by time I could even position myself on the bar stool. Putting the bottle down in front of me, the taste still in my mouth, fermented with a touch of sting, I could already feel the change in my body—it was as if my brain was telling my body to have a head start, the buzz started almost immediately. Twenty years later and I can still taste the beer on my lips, the scent still buried in my mind. Sometimes it feels like I was drinking yesterday. The club was always open in my mind, living near a college campus in the middle of a large city provided shortcuts that gave myself permission to duck away, to squeeze a few minutes of change that was needed, or so I thought at any given moment but usually I only allowed this to happen in the late afternoon. In my perception, I was a disciplined drinker. Eventually if I didn’t treat it, I grew grumpy, agitated and morose—these were the danger zones, an internal DMZ that could prove dangerous for my partner and myself. Drinking was a slow courting, eventually we were married, the bottle(s) and I, although for me it was a private matter that I tended to announce publicly. The Anyway Records tee-shirts during this time had an unofficial slogan on the back, “Buy Me a Beer” which was our joyous secret handshake to one another and for those who didn’t get it, well that was the point. But like all relationships, they must change, or they become dry, brittle and bitter by the time I was in my early thirties, with a gathering pile of dead friends and brokenness gathering around my path and with my own love story headed towards an oily ditch I had to make a choice.

At the edge of the slim hospital bed at the Shands detox center in Gainesville Florida, I grappled with the fact that it might be time to break-up with alcohol, which was terrifying as most break-ups are, and I was a person who avoided confrontation, plus I didn’t want to hurt her feelings. Who would take my place of the various barstools in Columbus, Athens and to a lesser extent, Gainesville? What would those bartenders do when they pushed a Black Label towards and empty seat, I was creating ghosts. There were the conversations I was having with myself, in retrospect it was both silly and tragic, this is where my behavior had taken me—constructing make-believe scenarios around liquid. But it was scary and coupled with depression and the burgeoning sense that a big part of my identity (I had tee-shirts made for Christ’s sake!), was being discarded, I was not only petrified but also on very shaky ground. Although later that night in the large cafeteria a sea of alcoholics, sitting on hard plastic chairs, sipping coffee from small Styrofoam cups, mixed with powder cream and packets of sugar that always seemed to spill half of their contents on the fake wooden fold up tables, I was offered and accepted hope. Although these small saplings of optimism were like virga, precipitation that evaporates before it hits the ground. So, the trick was to make sure that I had to feed the clouds so to speak, every day before the entire clouds of promise vanished. My years of going to bars, nightclubs and pubs had oddly equipped me with some of the behaviors I would use to stay sober, mostly that while a depressed introverted sort, I really liked being with other people, albeit at a distance, sometimes that unspoken space was a bottle of beer or two inches of Maker’s Mark. I used this learned behavior, the one that allowed me to feel invisible to do something different, to show up—to become a vessel that could water the cloud. Even though I very seldom trusted myself, my inability to fully understand my motivations was naked, raw and I borrowed other peoples, or should I say I copied it. After a year or so of sobriety, I investigated Buddhist practices, mostly meditation but did a great deal of reading and journaling—-and they worked, for many years afterwards, the depression left, evaporated into nothing. There would be moments of lucidity where I noticed the emptiness of where the depression had been like noticing a scar that has dissolved over time, and the relief I felt was an akin to a giant metaphysical sigh.

The rate of suicide attempts for children of parents who have completed suicide is 400% higher than those whose parents don’t complete suicide, and for people who experience a suicide in their lives, with friends and other family members there is a spike and it isn’t uncommon to see small mushroom clouds of despair that surround a completed suicide, the waves reach out and tap everybody within its orbit and then they too ripple around. If the person is a public figure the ripples continue far into the future, and for most these people it is the first remembrance of that person’s life, more so than even their greatest achievements whether it be music, acting or politics. The act provides a quiet permission that taking one’s own life is an option, it operates like a virus—thus the shame people feel when it is an ever-running option in their minds, as well as the shame for the people surrounding them. There is judgement, self and by others that presents itself as a solid stone mountain for dealing with those thoughts and especially the emotions that they come dressed in. Welcome to the Ball. For many substance users, for people that experience trauma and abandonment at an early age—we feel the actual physical environment differently than others, and this stems from an early age—we seek comfort from even the rooms we walk through and for me the primary one has been music, and it is the safest one. Even to this day, there is nothing more than I enjoy than driving my car listening to music and at times I want to sit in my partners drive way and hold her hand while I listen to Neil Young, Waxahatchee or any piece of music that comforts and inspires me, meanwhile she wants to get in the house, feed the kids, let the dog out, do things and I just want that little hand in mine and to listen. Or when I go to the gym, sit on the elliptical dance/running five or six miles to a soundtrack that I have created. I couldn’t not imagine living in the world pre-Walkman or phonographs. All those poor motherfuckers who lived before the mid-twentieth century, having to wait for wandering minstrels, or being able to afford orchestras—Jesus Christ how they must have suffered not knowing about the future of being able to listen to something whenever you wanted. But of course, it wasn’t just music I fell into to relieve my internal pain, it was alcohol, sex, the internet, buying things—even food—but all of them brought a different heat and different number of consequences, mostly feeding the black pool that has resided inside of me.

“Hurry up Bela, Jesus you are so slow,” Jenny was yapping at me while I looked for my car keys, summer was coming to a fast close, we were driving from Columbus to her hometown of South Vienna, I didn’t want to go—really had no intention of returning to anything that was near my high school. In my mind I had left the trappings of that building behind when I walked out the door just a few months earlier, and besides Jenny’s family and me soon to be divorced stepfather there was very little I wanted to see in that area save for a few friends. “I have your keys Nerdla!” she was already outside, yelling from the sidewalk—“C’mon!” While the fall brought the end of summer it also welcomed school, new friendships, football, and a change of clothing. She wore a short summer dress and sunglasses, her hair was still long—almost big but more scattered than most of the hairstyles that were so common in the mid to late eighties, mine was long and curly, I had not cut it for nearly seven months—since my senior pictures which was also the last time I have ever combed it. We drove the 40 minutes, listening to R.E.M. on the wheezing tape deck in my car, the fields of soy and corn waved and danced at us as we passed a forty-ounce Milwaukee’s Best between us, “should we stop and get another one?” she asked as she drank the last swig near London, Ohio. We sill had fifteen miles to go. “We can get some at Shoemaker’s” I said, referring to the now long closed supermarket in South Vienna. Jenny’s older sister worked there as her husband’s family owned it, years later after the giant Wal-Mart opened up six miles down the road the store came to a slow, sad and shuttering halt as if it were a slow-motion tumbleweed turning over in the wind. It was the annual South Vienna Corn Festival, something I had never attended while I was in high school, and while most of the other kids in school flocked to both the Corn Festival and the Clark County Fair, these were events that were a bit much too busy for me, if there is anything that makes an outsider feel more outside its an event that is filled with people. The more people there were, doing things I had no interest in the more I wanted to flee—-I’d rather be somewhere, anywhere else. But I was 18, in-love and so we went. Moving to rural Ohio from Athens, Ohio—yes, a small town but also a college town was difficult and in hindsight, almost traumatic for me—going from being able to walk everywhere, hang out in record stores, be privy to college students blaring music on their lawns while suntanning, drinking and laughing instilled the idea of a wider bigger and exciting world. I left Athens at the age of 14, in the early 80’s—and by that time I had discovered R rated movies—I had seen An American Werewolf in London, Apocalypse Now, and The Rocky Horror Picture Show, heard Bob Marley, The Clash, The Ramones and Devo. Suddenly I was transplanted into cornfields, and I felt like a scarecrow. At the Corn Festival I ran into my friend Chris Biester who was home for the long weekend from Ohio University, he had his guitar and played a few songs on the sidewalk—most notably “Sugar Mountain” which he explained was meaningful for him as he just turned twenty. At the time, on that hot September day—for those five minutes everything was alright, Chris’s voice and guitar held the air around me and while some of the passerby’s were no doubt looking askance at him, I never noticed. Twenty seemed far away from me even though I was 18, I would soon be stepping out of adolescence and Chris was already in adulthood. It was exciting, nerve wracking. I drank more beer.

The trips back to Western Ohio got less and less, in a few years Jenny and I had broken up—-she would return often as she struggled with homelessness and her mental health she would come back and stay with her mother—these were always short lived, maybe a week or two at best. One time, when she returned from an ill-fate trip to Miami where she had convinced an old bar-fly friend to fly her down to escape the streets of Columbus, a trip the ended with her being forced into Jackson County Memorial Hospital after being found wandering around delusional and drunk, I picked her up at the Columbus airport. “Well. I don’t think I can go back to Miami—there is nothing there for me. Not sure what I’ll do but I can stay with mom for a while.” Shortly though, she was back in Columbus—ducking in and out of Bernie’s and North Campus bars and taking up refuge in the ravines of Clintonville. “I can’t stay in South Vienna” she said one day as we walked towards the Tim Horton’s that sat between my house and her tent, “I’d rather be on the street than feel cooped up there.” “Maybe just staying with your mom would be good for you? You can quit drinking and there are less temptations?” “What if I don’t want to quit? Besides, there is nothing to do, just Mom’s boyfriend and the dog—what am I gonna do, work at Shoemaker’s?” Oddly, I saw her point. She had travelled all over the world, been to Europe countless times, lived in Spain for a few months, not as a student but she had run out of money and a kind Spanish woman welcomed her in until she finally got wrung out by Jenny being Jenny and bought her a ticket home. This was in the early nineties, another adventure Jenny had that peeled under the wheels of her life. Jenny had lived a million lives by the time she arrived at her mothers in 2005, broken and bent—she knew she was becoming a shell of her former self, the bits and cracks of her were dropping off of her everywhere, every night she went. “I love mom, but I’d rather take my chances in Columbus.”

There were times when we would talk, especially when she was really suffering—her skin bruised from the kind of living she did, she fell a lot—especially the last ten years of her life, not just from the alcohol but she was slowly using the use of her legs, she body thin from anemia and the inability of her to keep food in her body, it would erupt out of her when she tried to eat—it seemed she lived on vodka and Gatorade for most of her forties, “I can’t eat Bela, it doesn’t matter because I’m never very hungry.” Her hair was thinning, falling out in handfuls at times, the only part of her that seemed to be unchanged were her blue eyes, that still glowed while everything around them went dark, her body a leisurely collapse into nothingness, hers was like an abandoned village near Chernobyl, with only the trees still growing. She would look at me, disparage my depression as if I had some control over it, “I can’t understand why you want to die sometimes Bela, I just want to live soo much—-I wish I could still do the things I used to do.” She wore herself out trying to live, later—when she was near death, she told me just a few weeks before she died, the final almost continuous run of hospitalization was like a grotesque version of a baseball player’s hitting streak, “I can’t do this anymore, I just hurt so much. I don’t have it in me .” I could say nothing, just nod in silent agreement, she was battered—the thinness of her living had become too parched, the booze she had tried to quinch it with had only withered her insides.

Other times I would feel guilty when she said these things to me, as if I was robbing from her by being depressed, that one’s enthusiasm for living could be traded like a commodity. Later, I realized that moods are something I must learn to manage, that every day I drew away from my last drink was not always going to be better—I would have to encounter and persist through some dark times—but I knew if I had a drink it would allow the possibility of my inner doomsday machine to be activated. So, I haven’t. And I fill my days with laughter, regardless of how I might be feeling inside, I am always laughing, even alone—in the shower, on my walks, everywhere—I think if you know me, you know this much about me. I remarked to my partner recently that some people are like cut flowers, they sacrifice themselves to bring their beauty to others, cut at the stem, placed on a mantle, a coffee table, by the window for people to see-to smile, a courageous act. “There’s nothing courageous about it, they don’t have a choice to be cut—somebody just cuts them and sticks them in a vase.” Considering this, I thought about it, and just realized there is an acceptance then, it’s not aways a choice but there is beauty in existing and even in the slow melt of being in a vase, cut at the stem, brightly shining petals until they fall off. On March 8th, I will celebrate 20 years since my last drink.